|

|

|

I married a man who was stingy with his vowels. The drawl that had once made my toes curl and my legs open now grated the gentler parts of my reason. The rarity of his words made each one more valuable to me until waiting for him to speak became an obsession I could no longer bear.

I was lonely, and I wanted a child. In fact, I wanted a whole crop of children to fill this empty house with a richness of sound. Laughter, gossip, anger, and tears—I'd take it all and be thankful. A farm should have children. Silas remained stoic each month as my cycle came. But after that doctor in Rochester talked about low sperm count and poor motility, my husband had even less to say. His mulishness on this topic confused me, countering everything I had come to know about farming. I wasn't born to this life, but even I knew if you got bad seed, you didn't go on and plant it and pretend it was going to grow. You got new seed. Silas refused to discuss it. So last night, I'd taken the matter into my own hands. Evidence of my betrayal stained the sheets. Pollen. I could feel it. Smell it. Taste it. The promise of pollination had pulled me from my bed. Through the open window, I'd looked out over acres of corn. Moonlight and shadow played tricks in the fields, making the wide green blades look silver-blue. When the wind stirred, the gently rolling countryside appeared to ebb and flow beneath me. A well-plowed sea of fertility seemed to lap against the very foundation of our two-story clapboard. A slow, crawling itch worked its way down my inner thigh—a lingering trace of my husband, drying, dying. Reminding me, as if I could ever forget, of what he could not give me. Across the room, he'd slept, unconcerned. Most likely dreaming of corn, which was, to him, everything. I left him there and padded silently down the narrow back stairs, through the kitchen and out the mudroom door. Moving like a dreamer, I shed my clothes on the porch and walked naked into the corn. The cool furrowed ground soothed and calmed, inviting me deeper into the field. Long ribbons of green brushed my skin, raising exquisite trails of gooseflesh even as the sharp edges drew blood. Pollen dusted my body, collecting in drifts across my breasts and caking between my legs. Sticky silks rubbed my thighs. Low on the horizon, the heavy moon bathed me in milky light and I sparkled, covered in golden grains. It was then, for the first time in our eight-year marriage, that I thought I understood my husband's fascination. This fresh perspective filled me with a giddy eagerness, and I had the sense of being somewhat more than whole. Perhaps, if he would talk to me of nothing else, he would talk to me about corn. When I woke the next morning, satisfied for the first time in so many seasons, Silas was gone. I could tell by the forceful slant of sun streaming in through the window that the day already lacked my presence. I rose, mindful of the work to be done. I washed and dressed and gathered the linen from the bed before heading downstairs. In the kitchen, the clock over the stove read 7:14 a.m., later than I'd like. Farms ran on schedules and I was half an hour behind. Dishes in the sink told me Silas had breakfasted on cold kid cereal. The man loved that sugary junk and probably didn't miss his usual plate of hot eggs and sausage. But I missed him. There was this building energy inside me, as if I had important news I wanted to share. That, and I suddenly longed to be under the open sky, soaking in the sun. I grabbed a bottle of Coke from the icebox—Silas never did take to coffee, even with sugar—and set out to find my husband. The lights were on in our south outbuilding. I entered the hangar-sized garage and walked down the rows of sleeping harvesters, graders and plows. Near the far end, I saw Silas working on the sprayer tank, adjusting a hose that ran to a fifty-gallon drum sitting on a crate nearby. I hollered about the Coke and Silas looked up, but not at me. He stepped out from behind the assembly, focusing his attention on his boots, cracked leather, knotted lacings, worn-down heels. My husband didn't ever say much, but he was true as a man could be, and now with him not looking me in the eye, I knew he was troubled. "What've you done?" he said. His voice had been so low that if I hadn't been expecting those words, I wouldn't have heard them at all. As it was, he knew what I'd done. It hadn't been a question. I'd broken The Rule. Folks around here never cared much for anything that grew beyond their neighbors' hedgerows. Their country ways weathered generations, rusting into people's minds, becoming more law than lore. Most were toothless truisms on the order of the "early to bed, early to rise" variety. But there was one rule they held in profound and solemn regard—"Men raised corn and women stayed out of the fields." "Corn baby," he said. His words were as damning as any could be. "Mixed some herbicide." I could smell the sting of chemicals and I backed away from Silas and his drum of weed killer. A coldness washed over me as quickly as thunderclouds darken summer fields. Though sterile clinics hundreds of miles away explained my husband's inability to give me a child as a medical condition, in my heart, I suspected his love of that damned crop kept back the piece of him that would make him viable. If he chose corn above all else, so could I. I explained this to him with twice as many words as would fit in anyone's understanding. And when I finally had nothing left to say, I ran. He didn't pursue me. He seemed to have had his say that day in the outbuilding—five words that changed everything. But I could see the toll of what I'd done on his face. The lines around his eyes cut deeper and the corners of his mouth never lifted into a smile. I'd broken a precious thing, these gossamer bonds of my marriage. And I wondered at the bargain I'd struck—a child for my husband. But though my conscience ached, my heart refused to regret what I had done.

The ears grew fat. I grew fat. I craved honey—cloverleaf honey—constantly. Nothing else would do. Bees took an interest in me, swarming in clouds of curiosity. They never stung or even landed—they simply bumbled in the clover and watched. My honey consumption was such that it took me past the crossroads to the Piggly Wiggly once or twice a week. On those occasions, the locals—our neighbors, family, and friends—couldn't help but notice my increasing girth. After one such trip into town, driving home with a dozen crocks of honey, I pulled the truck off the road at our property line, just north on County Trunk J. Since that night, I hadn't broken The Rule again. I'd stayed out of the fields, but I couldn't resist being close by. I grabbed a honey jar and carefully climbed down from the cab. The ditch separating the road from the corn dipped low and I walked along its moist bottom, pushing through thickets of milkweed and wild mustard. An arm's length away, stalks towered overhead, creating a plaited canopy of green. Patches of light flickered between the rows, welcoming, teasing, as if inviting me in to stay. There was a gravity, being on the very edge of something so big, that held me there. I knew our acreage was absolute and finite. But I sensed infinity, too. The force of one kernel sprouting and giving life to a towering stalk awed me, and the energy each blade captured from the sun, a star almost ninety-three million miles away, was hard to imagine. I was wondering if I'd thought this way before, if Silas thought this way, when I became aware of a deep rumble behind me. I turned to see a familiar blue Dodge pull over and Mother Canter lean across to the open passenger-side window. Unlike her son, my mother-in-law never had a lack of words, and I learned then, standing in the ditch licking honey from my fingers, a surprising number of them were unkind. But what she screamed from the comfort of her truck cab was nothing I hadn't heard at backyard barbecues, Sunday dinners or church picnics. Folks loved to talk about The Rule. Their macabre tall tales told of monstrously deformed corn babies abandoned in the fields for the snakes, and of wombs turning into dried husks. I let her talk herself out. Her words held no sway with me. At that moment, all my attention focused inward: I felt my baby kick. Such a small thing, and yet so life changing. My body warmed as if liquid sunshine rushed through my veins and I wrapped my arms around my belly. If only Mother Canter could see this miracle the way I did, we might share the bond of motherhood. As one farm wife to another, our youth subject to the passing seasons, our backs bent to the yoke of household chores and our world limited, or not, by our obedience to The Rule, my heart went out to her. A silence passed between us. Then, though I never for a moment thought she'd say yes, I asked her if she would like to feel her grandbaby kick. My mother-in-law's actions spoke better than any words as she threw her truck into gear, her tires kicking back a spray of gravel that peppered my shins. I watched her speed down the road, no doubt to talk sense into her son. Minutes later, I heard the frantic clamor of our old farm bell calling Silas in from the field. Mother Canter had never, not even once, stepped foot into the corn.

Silas had begun watching me when he thought I wasn't looking. I found those chores of mine that required heavy lifting to be done in advance of my attention and objects too high to reach relocated to lower shelves. I thanked my silent husband for his kindness, and willed him to hear me. Which he did, finally, in early October. I was hanging the wash on the line, mindlessly humming along with the buzzing of the bees, when I noticed that my companions had multiplied in number from the usual dozen or so to a growing swarm roiling overhead. I had just pinned the last sheet and gathered the basket to go inside when my water broke. Contractions seized my insides and I panicked. That morning, Silas had taken the harvester to our eastern most hectare. I staggered across the dooryard to the bell. Frenzied bees trailed after me and I felt, for an instant, like a comet passing too close to the sun. I rang and rang, but labor came quicker than my husband. I squatted on the dusty ground and leaned against the bell pole. And so, on the last day of the harvest, our son was born. I gathered him in my skirts just as a shadow fell over us. Covered in chaff and dust, Silas stood before me looking so much like a product of the corn he loved. And so much like the man I knew—determined and single-minded. My heart longed for my husband to love this child, but my mind's eye saw only dark images of feasting carrion. I had been bold all those months ago, daring to break The Rule. But now, lying spent in the dirt, I discovered I was also fierce. I tilted our baby in my arms and introduced my husband to his son, Caleb. Wide-eyed and wordless, Silas took off his ball cap and craned his neck for a better look. Everything about our little boy was reed-like. Elegant fingers and toes—ten of each. An elongated head that came to a point in a way most babies' didn't. Long legs and arms that moved not in the typical uncoordinated jerks of newborns, but with a grace that suggested a soft summer breeze. Caleb's coloring, too, was different. Beautiful. His skin was milky and silky, and greenish-blond floss covered his scalp. His irises shone like polished jade and the whites of his eyes had a verdant cast. He didn't look like either of us. But he was ours. To my wonderment, our son thrived and grew. By Thanksgiving, his hair had thickened and darkened to a rich russet brown, just like corn silk in a late summer field. As the bitter winds blew across our land, we shuttered ourselves up snug inside. Sunlight, so brief and so welcome, graced our land as if rationed by a miser against the dark—and yet, the days themselves felt like eternity in passing. Nature slept under a thick blanket of snow, patiently waiting, as though each seed, each root, each rhizome, contained unbounded, unquestioned hope. I sensed Silas waited, too, though I knew not what he planned. He kept his distance—physically impossible in our modest farmhouse, but emotionally something at which he'd proven himself expert. Not only did he refuse the love and smiles so freely given by our son, but he withdrew from me, shunning the need I had for him. The silence grew so loud I could hear the cog works of my husband's inner reason as he lay awake in bed each night, not touching me, thinking thoughts he would not share. Motherhood, by itself, should have satisfied me. I wanted so much to be satisfied, to know that I'd done right. But nagging doubts of hubris came frequent and unbidden to my mind, and I wondered, after months of listening to nothing more than the whistling wind and the ticking mantel clock, if I had reached beyond my grasp.

To add to my grief, the plans Silas had made during the dark winter nights now become apparent. I bore the weight of his decision by watching him suffer, a good man, honest and hardworking, cut off from what he had been placed on this Earth to do. Seasons changed, but he never could—he'd been born a corn farmer, and he would die one. And yet, when the soil warmed, Silas planted wheat. Wheat, to punish me. And with that, I knew I had lost the last hope of his love. Yet, perhaps more devastating, as I weathered my own heartbreak I was forced to witness my husband's and know it was of my making. To me that spring, every part of him seemed smaller, withered and dry. As the tender green shoots of wheat appeared, looking so out of place in our fields, I watched Silas push on, forcing himself like a sprouting seed to do what must be done. The sun lingered in the sky and days grew in significance. Errant light slanted in through dirty windows and when I passed through the dusty beams, I felt a yearning akin to a deep, gnawing starvation. I longed to feel the warm, penetrating rays again. As soon as the last trill of winter played itself out, I took Caleb for a walk along the hedgerows. I remember, it was Easter Sunday, and I had hopes of gathering some wildflowers for the dinner table. We came upon a cluster of snow drops and I set Caleb down nearby in a thatch of new grass. I'd only turned away for a moment when I heard an unearthly melody, distinctly unlike the flirting twitter of sparrows, the low droning of bees, or even the distant rumble of tractors. The noise—music, really—felt the way I imagined happiness would. And it was coming from my son. He'd splayed his long toes in the mud and lifted his cherub face to the blue sky above. His tiny mouth hung open like a stop in a pan flute. He was humming. Later that day, I tried to describe for my husband what I had heard—the precious gift our son had given me. But before I could finish, Silas interrupted my prideful chatter, measuring out three brittle words. "Not 'our'—your," he said. True, Caleb was not of my husband's seed, but whether he knew it or not, the boy was of his heart. Corn was in their blood. I sliced them both dewy slabs of honey cake—my own sugar cravings ended with Caleb's birth—and wondered how Silas couldn't recognize his own son. Nurtured by the sun and my love, Caleb grew like a weed ranging between the furrows. Soon, he toddled by my side as I did my daily chores. The boy refused to wear shoes and went barefoot everywhere, letting dirt pack between his toes. His wordless melodies became the most beautiful music I'd ever heard. Whenever Caleb was particularly happy, he would hum. And I felt blessed that he hummed a good part of every day. Sometimes, Silas would turn an ear to listen. I imagined Caleb's music must be a siren's song to a corn farmer. My husband would sit back in his chair and for a moment, his shoulders would lose the tension they carried. But then, he'd catch me watching him, and suddenly work would call him away once more.

One afternoon as I hung the wash, I glimpsed Silas cutting across the yard, coming or going from some errand. As he neared, I felt a spark of foolish hope that he might be looking for me. So distracted was I by this girlish fantasy that it was a moment before I remembered Caleb standing next to me, reaching up to hand me a clothespin, and even longer before I noticed that he'd started to hum. And then, I detected harmony. I listened closely, suspecting a trick of the wind, perhaps air fluting through the rainspouts. But the resonance was distinctly baritone, rich and warm and almost unrecognizable in its scarcity. The sound was coming from my husband. If the heavens had broken at that moment, washing the land in sweet, gentle rain, I would have been no less surprised than at the concordance of father and son. Over the years, I'd learned that in this wide-open land, with nothing but crops and sky, the wind stole prayers as soon as they were given voice. I never imagined they'd be lofted high enough to reach the ears of God. From then on, Caleb became his father's son—so much so my heart ached with what I told myself was pride, but what I feared was despair. Caleb watched him, mesmerized, as if blinded by the sun. Farm life had shaped every aspect of my husband's demeanor, and I saw him reflected in our son in the economy of his stance, the modesty of his gestures, and even the very cadence of his breath. Silas took Caleb into the fields every day and I, a woman, was left alone to follow The Rule. I tried to be happy, but I was reminded of the irony of having gotten what I had wished for: Silas had finally opened his heart—only not to me. I battled the envy, and I am not proud to say I also harbored suspicion. However protective Silas was with Caleb, echoes of "corn baby" tickled my conscience and I did not trust him. I did not trust him because I knew for a sad fact that Caleb wasn't safe, even from his own mother. The bees had made me think of it. The harmless cloud that had followed me during my pregnancy now took no notice of me at all. Caleb was their true focus, the center of their small universe. They stayed a respectful distance away, reverent, never landing, never stinging, and I wondered what it was that fascinated them so. Except that I knew. Caleb, by his very nature, gave off an overwhelming scent of sweetness, which only seemed to intensify as he grew. It was this perfume of love and summer and sunshine that tempted me, in a moment of madness, to see if he tasted as sweet as he smelled. Only days before, I had nibbled on his toes too hard to be condoned as mere play, and sweet corn milk seeped from the tiny break in his skin. He stopped humming that instant and looked at me, surprise widening his green eyes. My misgivings, then, were founded on my guilt and nothing more, for Caleb flourished under his father's steady hand. He was no ordinary child, and grew faster than any other. Over hasty suppers of garden tomatoes, butter beans and bread, I'd steal hungry glances across the table, searching for lingering traces of my miracle baby, only to discover a leggy little boy instead. Between clumsy bites, he'd reward me with mischievous, wordless smiles that spoke volumes of his time in the fields. The very time of his childhood I came to covet, knowing that once it was gone, it was gone forever. Caleb was growing strong and straight and true—a farmer just like his father. And, just like his father, Caleb didn't need me. But I needed him, and I came to suspect Silas did too. Caleb's company, forever without words, but never without meaning, seemed to inspire my husband—my perennial hoarder of words—to loosen his tongue. "You ever watch corn grow?" he asked me one night. His voice sounded far away, coming as it did across the vast no-man's land that separated our bodies in the bed we shared. I thought at first he must be talking in his sleep, but when I looked at him, lit by the silver moon, his eyes were open, his gaze upon me. I asked him what he meant. "When I was a boy, I could never wait for the kernels to germinate. I'd dig them up to see if they'd sprouted, then replant them, good as new. "Every year, Lenore, I watched it grow, even though I knew how the story went. The first true blades appear one day like magic and the land takes on that green that only exists in a field of corn. Then the stalks grow, sometimes inches overnight. But the best part is when the tassels come. Then, I get this sobering sense that something of mine will go on." At that point, my husband rolled over and pulled up the counterpane. A moment of silence followed and I thought he'd fallen asleep when he said, "Caleb reminds me of that part."

Winter was mild and deceptively brief. By early March, unseasonable warmth had tempted plants and trees into an early bloom. But that spring was a cruel one. Tornadoes dug trenches and scattered neighboring homes. Hail dropped from the sky, pounding all nature of growing things. Blizzards of white cherry blossom petals rode the wind and plastered in wet clumps against our windowpanes. Winter wheat lay flattened and rotting in the fields. The only way to ever recover from such devastation is to repair, rebuild and replant. We could weather the loss. And so, my husband and his son went into the fields—the place where only men were allowed to go. They'd left me, Mother, Wife, Woman, to be revered in her lonely eerie, an empty nest.

Farmwives cannot afford the luxury of fashioning themselves a martyr—in my case, a Madonna sans child—so I pushed myself to work, to fill a void far greater than my own. The storms that spring had knocked every bloom from every branch, and now, in the midst of summer bounty, the bees faced famine. I found apiary kits for sale in the Montgomery Ward catalog and sent away for a dozen. Under the watchful sun, I cobbled together hutches and set out pools of sugared water to entice a queen and buy her lady-love. On the longest day of the year, the colony returned in force, buzzing in joyful tumult. They swarmed the bell pole, old friends reliving old times, before taking residence in the stout white boxes I'd set into the hedgerows. And, finally, when the hives began to pulse, needing a purpose and craving pollen, I watched, as yet another part of me disappeared into the fields, to go where I could not.

As the sun winked out on the western horizon, I took to tarrying in the dooryard, waiting for my men. The Perseids had returned with a bold show, the likes of which few had ever seen the equal, and I watched with dry, knowing eyes as stars dropped from the great indigo sky. The brashness of that autumn—the mirthful shades of copper, gold, and umber—mocked me and I felt undeserving of the harvest, as if I were attempting to reap what I had not sown. Winter was coming, and I found myself with no reserve of affection to see me through. Lean months of silence were all that waited. When the cold came, it set its teeth, fierce and relentless. We dug in as winter lingered, unwanted, into spring. Bees hibernated. Sap descended. Ponds froze. We feared the neglectful sun had forgotten us, tender, helpless creatures bent into the wind. Caleb became restless and Silas retreated, once again doling out words as if rationing them for some future time. I came to appreciate the subtle sounds my husband made—the slow rhythm of his sighs, the creak of his chair, the clearing of his throat—not as a precursor to speech, but simply as a reminder of his presence. Occasionally, I'd glance up from my work to check on him and find him checking on me, his weathered hands wrapped around a bottle of Coke. But then he'd turn his distant gaze to the frozen fields, and the moment, thinner than a whisper, would be lost. I spent my days in the kitchen, baking bread from a share of our wheat. Partly to feel the warmth the oven radiated into the room, and partly for something to busy my hands. I needed to feel productive. The simple repetition—knead, turn, knead, turn—was a welcome relief from the fullness of my thoughts and the emptiness of my heart. Then, just when I thought I could take no more of the desolate landscape and the bitter winds, I woke one morning to the patter of melt water. Icicles that had sheltered the winter tight to our eaves dripped with runoff, and the sun stuck adamantly in a big, blue sky. Drifts melted into rivulets and our fields became boggy. My world was once again filled with industry and music. Caleb and his father rediscovered their a cappella as they toiled through the waxing days, readying the fields. Pent up energy and simple, blessed joy propelled them, but watching Caleb shiver like a blade of grass in a gusty wind, I couldn't help but also feel a certain furtiveness about their efforts—as if they shared a secret. A secret apart from me. As the land woke slowly from the patient caresses of the plow, opening to accept seed, to make again life, I found myself skittish, haunted by a lack I couldn't define. I took to sleeping with the windows open, ignoring the damp chill of night. As I lay listening to the rhythmic croaking of frogs calling for mates, a distant train whistle added a haunting lyric to the night symphony and I was reminded of the world beyond these four walls—a world of life, energy, vibrancy. And of the lovely anguish of motherhood. My thoughts turned again to a child. A farm should have children. Perhaps, a girl this time. No, girls—fields and fields of them. A crop of daughters, to keep close to my heart—and out of the corn. My spirits swelled in readiness and in hope. Though Silas could not give me what I ached for, I knew I would not lie fallow. For those who choose this life, the distant sun is never farther away than the dawn. That spring, my husband planted corn.

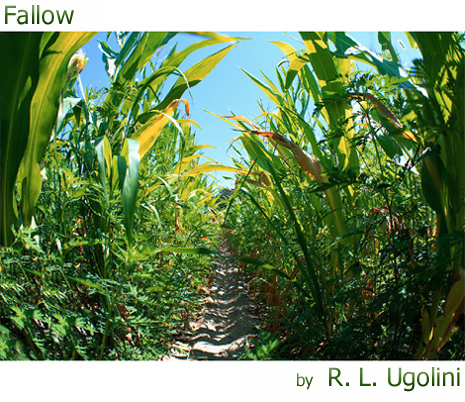

Title graphic: "Corn Maize" Copyright © The Summerset Review 2010. |

|