A Thursday in August in The Rio Grande Valley of Texas

Almost every day of the week now, I drive fast down 17 1/2 Mile Road, because it's the shortest distance between two worlds: mine and Reynaldo's. Today, I and my Jungian Shadow are late. I had to wait for my husband to get home from the office to take care of the children before I could leave the house. I couldn't hurry him because my whole family disapproves of how much time I spend with the witchdoctor. That's what they call my curanderoMexican or Mexican American healer, or "curer." S/he usually attends the impoverished Mexican Americans who hold traditional folk beliefs, and who are unlikely to have health insurance. "Good" curanderos/as are predominantly Catholics. "Bad" curanderos/as are called brujos/as, or witches., Reynaldo. My young son and daughter are already terrorized by my telling them Mexican folk tales. I thought they would enjoy stories such as La Llorona—The Crying Ghost of the mother who killed her children, and La Lechuza—The Witch in the form of an owl, but no, they don't. I have learned to keep my mouth shut around my family.

I had no idea what I was getting into when my neighbor, Rosie, introduced me to her cousin, Reynaldo Saenz, a tall, well-built man. When I first met him, I was surprised he was handsome and had white skin. I always thought witchdoctors were short with a dark tan. I have been taking careful notes over the past six months of researching Reynaldo as he heals el pobresThe "poor ones." Usually, el pobres are Mexican immigrants, whether legal or illegal, and including both short-term and long term—even generational—United States residents. The curandera/o is usually considered one of el pobres. in his consultorioConsulting room in which the spiritual tools, ingredients, and techniques of curanderismo are used. with intuition and compassion. I have come to appreciate the efficacy of his work in giving esperanza y salud, hope and health, to those Mexican immigrants who have crossed the border into the U.S.—some across the international bridges, some across the Rio Grande River. I've developed a deep respect for Reynaldo, and that's not all. He has become my hero. He's always dressed in white, even with tennis shoes.

I'm slipping in some areas of everyday responsibilities because I've made Reynaldo a priority, but I'm not convinced this is a bad thing. Yesterday, I had declined an invitation to lunch with my friends at the country club in order to take Reynaldo to Walmart for groceries—he doesn't own a car. He can catch rides from a lot of his clients, but he says he likes being interviewed by me as he drives my Tahoe. Then, today, I'm skipping Quintanilla's Mexican American Folklore class. I figure ethnographic field research on this curandero, a fine specimen of a folk healer living here on the South Texas border of Mexico, contributes more weightily to my Master's thesis in Anthropology than does a classroom lecture.

We're not even trying to miss the potholes on this country dirt road this afternoon, because at seventy miles per hour, the Tahoe's tires skim right over them. My Shadow, constituted by those repressions stuffed down deep into my psyche by my White Anglo Saxon Protestant culture's proscriptions, is longing for communion with the magical world view of Mexican folk culture, where witches, demons, and spirits are constant companions. And from within which Reynaldo is known for working his own special brand of magic: exorcism.

When I arrive this afternoon and brake in the Saenz's caliche drive with gravel-spraying energy, I see a statue of St. Joseph the Carpenter. On the porch, next to his white, wood framed house, Reynaldo is bent over a table hammering something. I guess so much exposure to santos, folk saints, can create hallucinations.

"Hi, Katherine. Lucy's inside doing a card reading. We won't bother her until she's finished."

So much for hallucinating! Lucy, Reynaldo's cute wife, doesn't seem like Joseph's wife. But I acknowledge that at least this time, Lucy's tarot cards don't bother me as much as they did a month ago. This tolerance for my playing in the devil's playpen is perhaps making me compromise my Christian principles. However, remembering Dr. Quintanilla's lectures on cultural relativity, I'm now accepting Lucy's card reading as part of her culture. I recognize that I, myself, am acculturating as I spend more quality time immersed in the life of a curandero. Still, the surprise that even principles seem culturally relative worries me some. I really don't want to die and go to hell.

Reynaldo's workbench is a rusty old bar fridge at the far end of the porch. I see he is tacking down into the wood the brass crucifix of his handheld cross. It had become separated. Sweat is dripping off his nose onto the cross; his white shirt is grey with dampness at the armpits. The wind is blowing hard enough to stick his salt-and-pepper hair up on the crown of his head like rooster feathers.

He pauses in his tapping to tell me, "Sometimes the demons are powerful enough to even damage my cross. I'll show you the first metal one they truly destroyed. I keep it as a reminder of their power. A strong demon spirit that I was trying to exorcise split it right in two! It exploded in my hand! I'm lucky to be alive!" Reynaldo says all this with great excitement. "I switched to this cross after that happened because wood absorbs the spiritual fluids." He finishes his tapping and invites me to accompany him to return the repaired cross to the trono, throne.

We walk side by side under the mesquite arbor on the way to the consultorio.

"I prayed for a fight with the devil, once," I tell Reynaldo with as much humility as I can muster.

"Oh? Why?"

"At the time I felt courageous and strong. Morally superior. Self-righteous."

"I understand that." Reynaldo sets the repaired cross on the arm of his white, homemade, wooden throne. It's obvious he doesn't think that praying for a fight with the devil is so unusual. "And what happened?" he asks.

"Nothing. Well, I was surprised the other women at the altar rail seemed horrified. I thought they would cheer for my heroism. And Father Robert asked God to grant me humility. Then he signed the cross on my forehead with his thumb like he was hitting a bull's eye."

As we walk back toward the house, I weigh the odds of Reynaldo understanding Jungian concepts about The Shadow. I decide it is worth a shot because it's important information when defending my thesis, theoretically.

"I study Jung, Reynaldo. Jung was a psychoanalyst from Zurich who says that evil is not really evil, but those contents of the psyche which have to erupt, unbidden, into consciousness, because of too much pressure built up under psychological repressions. Jung symbolizes the repressions as "The Shadow." In real life, the repressed feelings can come out distorted in the form of a neurosis, maybe even a psychosis. Ideally, if you can channel your emotions appropriately into the light of day, you can become fully human. Otherwise you might end up acting like a demon." I listen carefully for Reynaldo's response.

"Who is this Jung? What spirit does he channel?" Reynaldo asks with what is apparently first time, lively interest. "He sounds very smart. Is he still alive?"

"No. He died in the 1960s. But I guess you could say he helped his patients channel their own spirits."

Reynaldo stops under a mesquite tree and looks at me with inquisitive, long-lashed brown eyes. "You know, I think I could channel Jung's spirit. What was his first name? Do you have any books with pictures of Jung?"

It would be a momentous occasion to see Reynaldo channel Carl Gustav Jung's spirit. So I agree to bring him some books with pictures, just to see what he can do with it. Reynaldo continues walking and talking, with me behind him, trying to keep a straight face.

"Emotions are one thing, but the devil is another." Reynaldo swivels to put a hand on my back to catch me up with him. "Some ailments, like desesperaciónDepression. and angustoAnxiety., can be healed with psychology—I do it all the time—but not demon possession. The devil and his army of demons are real, whether you believe in him or not. He's not a myth like Santa Claus. I know. I have fought the demons in person. Several times. I'm known as the Exorcist of Edinburg! Me! Reynaldo!" He sticks out his chest.

"Then why don't you exorcise Victor Camacho?" Doctor Camacho is the powerful professor in my graduate program with whom I am battling for ownership of that intellectual property which is called Reynaldo Saenz. "Oh, right, you can't exorcise him because he is the devil!" And I laugh until I bend over, holding my stomach. It makes Reynaldo chuckle, even though we both know Camacho will probably win the property.

We walk a little farther, then Reynaldo stops and surprises me by taking my hand and holding it in his. "You are beautiful, Katherine. Beautiful blue eyes." A rush of heat consumes me. My heart must be cartoonishly beating right through my chest because he then says, "And you have a beautiful heart."

Reynaldo gazes at me, studies me, and seems to come to a decision. "Tomorrow, I am performing an exorcism. I would like you to bring your video camera for the occasion. Can you do that for me? You can put on your anthropologist hat. Not even Victor has ever videoed one of my exorcisms. "

This is more like it. What better way to spend a Friday than videotaping an exorcism?

Friday, The Exorcism

Juanita is a square, porcine, simple-minded, forty-year-old girl—not a woman—and still a virgin. Her relationship with Jesus is intact, despite the fact she has been possessed for twenty years by a demon—a demon that manifests itself primarily when Juanita enters a church, and causes her behavior to escalate into violence if she approaches the altar to receive the Eucharist. She once bit the priest as he laid the Corpo de CristeEucharistic wafer symbolizing the body of Christ. on her tongue.

"No! No! No!" Juanita hollers, pummeling Reynaldo's chest as he reads from a leather-bound book held in his right hand, owl glasses perched learnedly on his nose, handheld cross elevated in his left hand. I switch on the video camera, and walk across the expanse of yard toward the consultorio where the exorcism has apparently already begun.

From a decreasing distance, I pan from Reynaldo to Juanita to Juanita's sister, Yoli, who is trying to restrain Juanita, then over to two old women who are sitting on the outdoor waiting bench wearing smock house dresses and flip-flops. Their backs are to the consultorio so as to direct their chanted prayers to the characters on stage under the arbor of mesquites. Bob, the dog, is sitting on his haunches in the middle of the hubbub. He looks menacing when he growls at Juanita.

Reynaldo exhibits an inner strength that is as palpable as Juanita's pummeling. I know without a doubt that it is just such inner strength of which heroes are made. The kind of strength required to look evil in the face and patiently out-wait the devil. The kind of strength required to defeat such an inordinate enemy as a demon—or a teenager. Jung calls it "holding the tension" and promises that if one can hold on long enough in the face of psychic agitation, transformation will happen. Today, it is obvious that Reynaldo has achieved a transformation. He towers over Juanita—the demon—who is losing it in the face of Reynaldo's indomitable authority.

When I reach the action, the exorcist keeps reading, but half closes the leather-bound book, sidles over to the camera, and holds it in front of the lens so I can capture its title, "The Holy Rite of Exorcism." The mesquite leaves dapple the letters with shadows. I realize that Reynaldo has been reading from this missal in English, not Spanish. Besides the defense of his wooden handheld cross, Reynaldo is wearing a gigantic wooden rosary around his neck, the kind the vendors sell on the streets across the border in Nuevo Progresso. "Wood absorbs the spiritual fluids," I remember him saying.

This poor demon is a pansy, definitely not the caliber of the one in The Exorcist, the movie I've been mentally reviewing as my only exposure to exorcisms.

"The demon seems very weak, Reynaldo."

"That is a good observation, Katherine," he says to the camera. "He is getting worn down by Juanita's strong faith—and also as a result of the many attacks I've made on him over a four-month period. Once he tells me his name, I will have defeated him for good. But for now, my instincts tell me he is Asterot, Lord of Lust and confusion, a greater demon in Satan's military."

Reynaldo returns to reading in the face of weak protestations from the demon. On and on and on, page after page he reads. Yoli yawns. Juanita sits down on the picnic bench, half-heartedly moaning every once in a while. For about thirty minutes, the most interesting thing is Reynaldo flipping a page, or pushing his glasses higher on the bridge of his nose with his middle finger as he reads on and on and on.

My arms grow tired from holding the camera. I lower it, backing up toward the picnic table in order to sit down and join the demon for a break. When Reynaldo sees me doing this, he rushes over. He grabs a plastic flask with "Holy Water" embossed across it in gold. He must have watched The Exorcist, too, because as he flicks water on the demon, he intones in Spanish sprinkled with Latin, "En el nombre del Padre" (flick), "del Filii" (flick), "y Espiriti Sancti""In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit." (flick flick).

Juanita jumps up in shock, and then throws herself to the dusty ground, screaming and writhing. This is where her head should turn around on her shoulders, but it never does. I realize I entertained the idea that it might. Reynaldo and Yoli hit the dirt with her, trying to restrain the demon. All three are thrashing around in battle on the ground, dust flying. I, too, from a safe distance, instinctively drop down with them to get an eye-level shot with the video camera. The demon screams loudly; the women on the waiting bench pray loudly; and the exorcist sprinkles salt on Juanita. The demon's fury escalates into a psychotic rage.

Reynaldo yells, "Get back, Katherine! Move away!"

"What?" I mumble from where I sit cross-legged on the ground, frantically trying to cue the tape to where I left off. I ignore Reynaldo's warning because the action is too good to miss.

Juanita breaks free from her sister's prone scissor hold. Her white shorts provide no cushion to her flabby knees as she makes a crawling break for it and heads directly at me like a freight train, her butt jiggling like massive Jell-O, and her large breasts swinging from side to side between her scrambling arms. She's snorting gasps of breath. Mad pig! Mad pig! She looks directly into the camera as she charges toward me, and if I'd never seen a demon before I'm sure I've seen one now. I also realize it's too late to rise and run.

"Get back, Katherine! You are not wearing a cuerda. You are not protected!" The exorcist jumps up and replaces the salt shaker in his hand with the bottle of blessed olive oil. He swings around to jump and lands right between me and the demon, arms akimbo. Surprised, the demon brakes and looks up from Juanita's pig stance at Reynaldo. Reynaldo makes the sign of the cross with his thumb on her forehead like he's hitting a bull's eye. Immediately, Juanita rolls onto her side on the hard dirt and indulges in soft sobs. The two old women--who I half suspected were hired characters for the performance, that have been praying during the entire long exorcism--now move toward the entrance of the consultorio to wait their turn and see Reynaldo, the curandero, as if nothing has happened.

Juanita sits on the picnic bench, the accoutrements of exorcism displayed behind her, a perfect video shot. She's smiling through teary eyes. Yoli wipes her face with a wet rag, just as I used to wipe my children's faces. Juanita even looks pretty. I'm very moved by her apparent release from the psychotic rage that recently possessed her. This contrast is what jolts me into some sort of acceptance of exorcism as a means of remediating the Jungian Shadow—exorcism along with a little theatrical expunging.

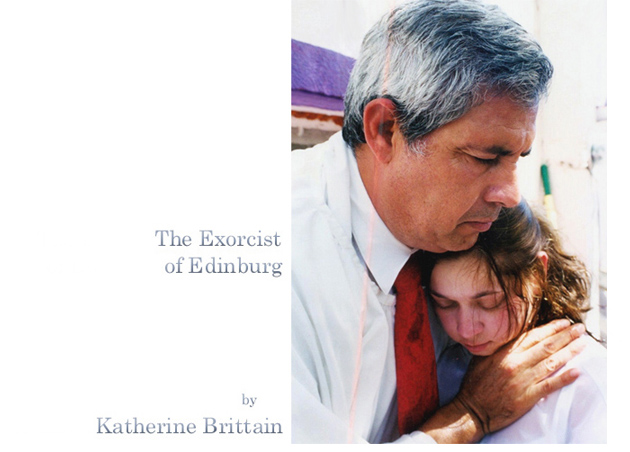

Reynaldo kneels before Juanita and pours some Holy Water on her bleeding knees. He pulls a white cup towel from his back pocket and oh, so tenderly, he dabs away the blood. I feel intimately connected to them through the lens and a lump clicks in my throat. Reynaldo pours more Holy Water and gently wipes away the dust and grime from her telephone pole legs. Jesus washing the disciple's feet. The comparison of Reynaldo with Jesus is solid. I can't escape the illusion.

"It's okay to love Jesus that way," Carmen, the Basque nun from Corpus Christi had told me last June when I went to the Monastery for spiritual direction about how to be a monk. I don't like nuns.

Even from behind the camera, my body heats up, signaling that what I am experiencing is deseo, desire. Who would think such a tender show of compassion could be such a turn-on? It's not right. It's just not right.

The last thing I video this day is Juanita and Yoli walking slowly off into the sunset, Juanita's butt jiggly-swishing from side to side.

Reynaldo has closed the door to the consultorio. When he lights the santita candles on the altar, the glowing, wavering mood suggests we now exist in another spiritual dimension of engaged senses. He has me start the copal incense in the handmade brazier next to him. Tendrils of smoke mystically interact with his body as he sits in el trono, leaning forward, arms on his thighs, hands clasped between his spread knees. He ignores the women, and reaches for my hand to guide me in front of him. "What do you think of my work?" he asks, looking into my eyes. But he doesn't wait for an answer. "An exorcism requires the human touch. This particular battle was won when Juanita decided she wanted to remain in the earthly realm. Only another human can influence that choice. It's all in the eye contact. The eyes are the window to the soul. Did you film the whole thing?"

I nod while my soul falls into his eyes.

"When we watch it together, you will see how often Juanita and I make eye contact."

Reynaldo is so tender with the old women. My eyes sting with appreciation for his compassion, but then I remember I don't cry. One woman has arthritis and Reynaldo massages her gnarled fingers with homemade pomade while praying the Padre Nuestre, The Lord's Prayer. The other is having trouble sleeping, and Reynaldo first sweeps her with rosemary sprigs, spiritually cleansing her. Then he gives her a written prescription for an herbal tea which she can fill at a yerberia, a Mexican drugstore.

The rest of our time in the consultorio is spent with me trying to repress my feelings of deseo so I can have a rational conversation with Reynaldo. But my Shadow is pushing for communion with the authoritative, heroic, tender exorcist.

Images appear courtesy of Katherine Brittain.