I am standing on the boardwalk that surrounds Old Faithful, trying to convince my two toddlers to be patient: chasing them around, carrying them on my shoulders, bribing them with candy, begging them to just stay put and wait, because any minute now, really soon, they'll see it, one of the wonders of nature. When it finally does erupt, Isaak stares at it for about four seconds, and then, loud enough for everyone to hear, says: "Can we go to Walmart?"

Our feeling for nature resembles the feeling of the sick for health.

—Friedrich Schiller

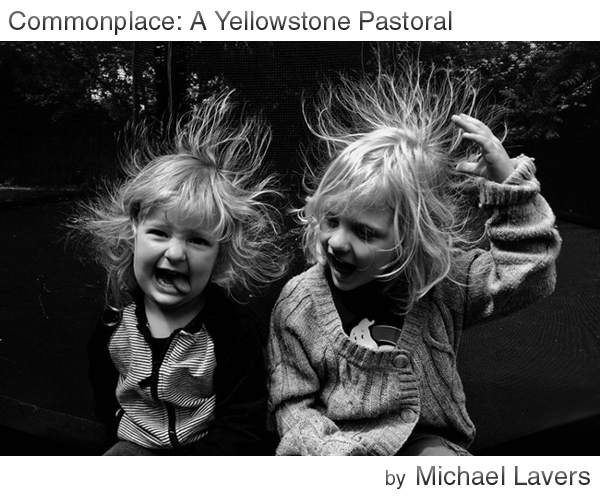

One week before this, I'm lying on the sofa Claire and I have begun to fight about: its spots and stains, the large tear up the side where foam kept leaking like a yellow puss vs. its perfect armrests and cradling form. Our kids orbit the sprinkler, the summer heat wave making all their moods unstable, like the static in the air before a storm. Magda is two, Isaak four.

...the weariness, the fever, and the fret...

—John Keats

So we packed the car and locked the house and drove into the woods. We'd see if we could disappear.

Buffalo Campground is a series of kidney-shaped loops, and each loop has nine or ten plots. Each plot has a picnic table, a fire pit and a flat square of hardish earth meant for tents. All food, food scraps, food wrappers, and food waste must be kept in the car, or deposited in the bear-proof dumpster next to the restrooms. Flush toilets, electric and sewage hook-up. My sister and her family have reserved the campsite next to ours. I set up our tent and we wait for them to arrive.

Resting on the frame of the camp water spigot is a small bar of soap with a black hair on it. When I turn around, Isaak is playing with it, pretending the bar of soap is a car.

A black ant biting into the neck of an amber-colored grub, about an inch long, writhing helplessly under the attack of its much smaller predator. Claire: "Little scenes of horror everywhere."

Musquetoes extreemly troublesome.

—Meriwether Lewis

The number of Disney/Pixar Cars figures we brought from home, combined with those newly gifted on this trip to keep them occupied, totals eleven. Isaak's favorite alternates between Mater and Lightning McQueen, and Magda's between Sally, Lightning McQueen, and the yellow Cruz Ramirez. They make the trip both feasible and frustrating, since about forty percent of my mental energy is spent safeguarding these toys, making sure our kids don't drop them in the bushes or into the river. Keeping track of them is only slightly less stressful than what would happen if one of them got lost.

It is fortunate for us, however, that Nature is so imperfect, as otherwise we should have no art at all.

—Oscar Wilde

I thought that if I could put it all down, that would be one way. And next the thought came to me that to leave all out, would be another, and truer, way.

—John Ashbery

Picking graham cracker crumbs out of the gravel so the bears don't come.

Claire taking photos of the wild rye.

Buffalo River. Watching the grebes, hearing the lodgepoles creek, the ducks and geese cavorting down the shore. Staring at the faint blue shadow of the mountain as the sun begins its downward tilt.

The misquitoes and Ticks are noumerous and bad.

—William Clarke

Melted chocolate in Isaak's bangs, which hang down into his mouth.

Mid-thirties that first night, and so the tent became a mixture of cold sweat and hot breath. And all night long the low hum of generators next door.

A single crow from four-to-six am. Caw caw caw caw.

We must therefore use some illusion to render a pastoral delightful; and this consists in exposing the best side only of a shepherd's life, and in concealing its miseries.

—Alexander Pope

Claire, afraid of bears, peed into a plastic bag in the tent in the middle of the night, which of course leaked, and now my pants and Isaak's jacket are drying in the sun.

An act to set apart a certain tract of land lying near the headwaters of the Yellowstone River as a public park...or pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.

—Act Establishing Yellowstone National Park

The first thing you notice when you enter Yellowstone is the traffic, the traffic and the crowds, and how inadequate the little strip of highway is in the face of almost four million visitors per year. According to the National Park Service website, June alone sees 700,000 visitors. Assuming an average of four visitors per vehicle, Yellowstone will see roughly 175,000 cars pass through this month. About 5,800 new cars per day, all sharing more or less the same road.

It is grand, gloomy, and terrible; a solitude peopled with fantastic ideas; an empire of shadows and of turmoil.

—Lieut. G. C. Doane in

Yellowstone, August 26, 1870

Today I am in the Yellowstone Park, and I wish I were dead.

—Rudyard Kipling

The Paint Pots nature trail has an undersized parking lot, which causes traffic to back up onto the main highway. It takes us roughly forty minutes to enter the lot and find a place to park, and then another forty minutes to walk the half-mile kilometer boardwalk trail, which is as crowded as any big city sidewalk. We put the kids in the chariot, and push them for a while, but they soon want out. This is a problem, because the boardwalk has no railings, and the pools of boiling hot water are sometimes just a few feet away from the trail. I end up holding them so tightly by the wrists that their hands turned as white as my knuckles, while they rev and try to zoom away like Lightning McQueen and Cruz Ramirez, the circular boardwalk looking very much like a racetrack.

Hour thirty, and roughly that many mosquito bites. A rate that actually seems rather slow.

Old Faithful is sometimes degraded by being made a laundry. Garments placed in the crater during quiescence are ejected thoroughly washed when the eruption takes place. Gen. Sheridan's men, in 1882, found that linen and cotton fabrics were uninjured by the action of the water, but woolen clothes were torn to shreds.

—Henry J. Winser

Thoreau would take his laundry back to Concord for his mother to wash.

Three separate groups of Asian women freeze and stare and coo when Magda walks by. She is two years old, with an oversized poof of curly gold-colored hair. One woman hushed a group of seven or eight of her friends and directed their attention to my daughter, after which they all began to point at her and talk, and not quietly.

People drinking orange and pink Slurpees on the boardwalk.

"Can we go to Walmart?"

We cannot find our car. Isaak on my shoulders, fifty pounds of bored and restless and tired and top-heavy muscle hanging off me in the hot afternoon sun as I wander up and down the rows of the crowded lot, looking and looking.

Naps in the car on the way back to the campground.

Claire by the fire, stirring a pot of soup.

Evening. Woodsmoke. Lake Island Reservoir the color of cold, colorless tea. Low mountains to the west shedding their ice. A table and two wooden chairs, a cake with just a hint of icing. The last of the apples, the last of the milk.

I'm reading Emerson: "Nature is the incarnation of a thought, and turns to a thought again, as ice becomes water and gas. The world is mind precipitated..."

The moon swiveling its spotlight on the hill.

Yampa blooms.

Everything I have written seems false.

Just when I thought he'd fallen asleep:

—Dad

—What, Isaak?

—I'm not Isaak. I'm Lightning McQueen. I'm Lightning McQueen, and you're Mater.

Only now, in his fourth year, is he composing sentences. Before this he would squint and shake his head and raise his hands and flail them, as if they were a pull cord and could tug the engine of his tongue into a kind of fluency. So after all that silence, these sentences strike me as profoundly beautiful, voluminous, and true. And so I willingly submit to these assigned roles, spending most of his fourth year of life pretending we are who we aren't.

Magda following Isaak like a feeder fish as they wade in the water by the dock.

Claire's swimsuit, slung over a poplar bough to dry, dangling in the moonlight like a lost saffron medusa.

Sandhill cranes.

"Lakeside Cottage": three beds, two baths for our two families, a full kitchen and wrap-around deck, with private access to Island Park Reservoir. There's a thirty-foot dock, on which a green canoe rests upside down. Snowshoes hang on the wall, old sepia family photos and paintings of the local scenery, all signed "S. Packer." All the cupboards in the kitchen have labels like "flour and sugar" or "foils and wraps," and all the bedsheets have been labeled in permanent marker: "Lakeside Cottage master bed," "Lakeside Cottage pullout." There's Wi-Fi, a satellite dish, a forty- inch TV with Blu-ray/DVD player.

The Musqueters large and very troublesome.

—William Clarke

Isaak and Magda are on a large boulder, pretending that ground around them is lava, and they have to stay put, and not let go of each other, not ever. Except for water, maybe, and a little food. And maybe a dropped car or forgotten truck, as if the toy held the key to saving you, or else simply needed to be in hand when the lava rises and the end comes.

Swimming and wading at the boat launch. Lunch at McDonalds, a playground in West Yellowstone, groceries, canoeing around the dock and the cabin, watching the water-skiers pass. By four o'clock we're drying off, watching How to Train Your Dragon 2.

The city is like Augustine's God, a circle whose center is everywhere, and its circumference nowhere.

The sun is setting behind the mountains. What blue has not dissolved is right above us. Cobalt in the east, and in the west an undiluted pink and gold pouring up over the mountain's lip.

S. Packer's masterpiece, as least out of the work I've seen—about a dozen samples—hangs above the fireplace in the living room. It's roughly two by three feet and depicts a late autumn landscape covered with snow in which a single cowboy rides along the edge of river, leading a pack horse behind him. The horse he rides is white, just slightly grayer than the snow, the river a greyish rust-colored blue that bleeds into a swampy communal brown, with a layer of dead bright-orange leaves coating the bottom.

One of the books on the shelves at Lakeside Cottage, next to all the romances, spy thrillers, and field guides, is a 1120-page novel called Prairie (subtitle: "The Legend of Charles Burton Irwin and the Y6 Ranch") by Anna Lee Waldo. The front cover proclaims it as a New York Times Bestseller. From the back cover: "Charles Burton Irwin. An American legend. He was a leader of men and a lover of adventure. With his wife and children at his side, he grabbed hold of the reins of change and rode the wild American west into a new frontier—the 20th century."

In 1855, Washington Territorial Governor, Isaac I. Stevens, responding to increasing white expansion, negotiated a treaty with the Nex Perce chiefs, recognizing their peoples' right to their traditional homeland and establishing it as a reservation of some 5,000 square miles.

—The Nez Perce National Historic Trail brochure.

First the labourers are removed from the land, and then the sheep arrive.

—Karl Marx

Day five. We attempt a picnic at Gibbon Falls, a place roughly twenty minutes inside the park's west entrance. We feel our kids might be up for this. We feel this is about what they could endure, what they could indulge us with. We don't know it's a terrible place for a picnic: no grassy knoll, no picnic tables, no quiet glade. There are instead about three hundred cars, a stone wall lining a hundred yards of paved walkway, along which people come and go as if a baseball game had just let out. Claire and I park, get our kids out of the car, and try desperately to hold them by the hand so that they don't mount the tree-foot stone wall and pitch themselves over into the gorge below. We take turns inhaling sandwiches and keeping the kids safe, then we get back in the car and give them fruit leather and fish crackers for the drive home.

The tourists...poured into that place with a joyful whoop, and, scarce washing the dust from themselves, began to celebrate the 4th of July...The clergyman rose up and told them they were the greatest, freeset, sublimest, most chivalrous, and richest people on the face of the earth, and they all said Amen.

—Rudyard Kipling

Incomprehensible, the things of this world.

The Grizzly and Wolf Discovery Center in West Yellowstone, Montana houses eight live grizzlies: Sam, Kobuk, Nakina, Spirit, Sow 101, Coram, and the brothers Grant and Roosevelt. There are also three wolf "packs," consisting of only two wolves each, each pack in its own small backyard-sized habitat. On the day we visit, all of the wolves are asleep, or trying to sleep. There are various bones scattered throughout their habitats, vertebrae licked clean, smooth grey rib cages and several skulls. One of the wolves is dozing right next to an uneaten rack of ribs and a beet-red steak about six inches thick. A sign tells us these wolves were raised in captivity, and would not survive if returned to the wild.

Near the grizzly enclosure, I hear one of the center's wardens or rangers explain to a family in khaki shorts and ponchos: "Never use bear spray at your campsite, because when it dries it smells like pepper, and that will draw more in."

Back at the cabin, one of those believe-it-or-not shows highlighting the cutting edge of natural and scientific weirdness. We learn about a farm in Utah—out of Utah State University in Logan—where researchers have implanted genes from golden orb-weaver spiders into goats. The harvested milk is then centrifuged, the spider silk extracted out of it, and then spun onto a giant spool. This method of harvesting the silk was invented because spiders are too territorial to be farmed large-scale. The high-strength silk has been trademarked as BioSteel, is seven-to-ten times as strong as regular steel, and can stretch up to twenty times its size—in temperatures ranging from minus twenty to 330 degrees Celsius—without compromising its strength.

Nature is not natural, and can never be naturalized.

—Graham Harman

A stray dog, half-brown and half-black, hovers for a while around our cabin. We make various attempts to spook him away, but he looks as at home here as me, unsure of where he stands or how to move.

I ask Isaak to draw me a picture of whatever he wants. He draws this, and says it's Lightning McQueen.

I ask Magda to do the same, and she tells me this is a geyser:

In the afternoon of day seven we go back into West Yellowstone, and our car battery dies. I call roadside assistance and a truck is there in twenty minutes. I watch the man recharge our battery, feeling slightly ashamed of my ignorance and helplessness, thinking of Charles Burton Irwin, American Legend. With his wife and children at his side, he grabbed hold of the reins of change and rode the wild American west into a new frontier—the 20th century.

It is very unhappy, but too late to be helped, the discovery we have made, that we exist.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

This day I completed my thirty first year, and conceived that I had in all human probability now existed about half the period which I am to remain in this Sublunary world. I reflected that I had as yet done but little, very little indeed, to further the hapiness of the human race, or to advance the information of the succeeding generation.

—Meriwether Lewis

I sleep badly the last night. Shivering and feverish, probably from being under-slept in tents and cabins with seven young children all week. This passes by morning, and I'm well enough to drive home.

Stopping for gas on the way out, I scroll through Claire's photos of the week: pelicans mid-air above the lake; Isaak in his blue pajamas leaning on a tree, Magda and me hanging our feet over the dock.

Aloe vera: $18.54; chamomile lotion: $8.45; Band-Aids: $3.17.

Nature...exacts / her tribute of inevitable pain.

—William Wordsworth

The prairie and its rush-hour of images. Then cities again. We stop in Ogden at Walmart, as requested, and they skip through the toy aisles in total glee, happier than they've been all week.

Earth has not anything to show more fair...This City now doth, like a garment, wear / The beauty of the morning...

—William Wordsworth

True paradises are the paradises we have lost.

—Marcel Proust

The house on Locust Lane, just as we left it: the Scotch pine in the front, the rosebushes out back.

And all their lands restored to them again / That were with him exiled.

—Shakespeare, As You Like It

I walk inside. Here is the couch, waiting for us with its patina of stains.

And there through the window is Claire, already dropping eggshell shards around the strawberries to keep the snails at bay.

And there is Isaak running after Magda through the sprinklers, cavorting in the spray, and letting fall into the grass that small menagerie of his, his die-cast Maters and his scuffed McQueens.

Now comes the gloaming. The alpenglow is fading into earthy, murky gloom, but do not let your town habits draw you away to the hotel. Stay on this good fire-mountain and spend the night among the stars. Watch their glorious bloom until the dawn, and get one more baptism of light. Then, with fresh heart, go down to your work, and whatever your fate, under whatever ignorance or knowledge you may afterward chance to suffer, you will remember these fine, wild views, and look back with joy to your wanderings in the blessed old Yellowstone Wonderland.

—John Muir

Images provided courtesy of Michael Lavers.